Lament

October 11th, 2014 - November 8, 2014 at Leon Gallery, Denver, CO

photos by Amanda Tipton

Statement

In 2013, the oil and gas industry in the United States was responsible for an average of approximately twenty oil spills per day. However: that’s only accounting for the ones we know of, as many oil-producing states don’t require reporting to the public. The most reported on oil spill of all, the Deepwater Horizon spill of 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico, still wreaks havoc in our environment, despite propaganda to the contrary and claims of over 210 million gallons of crude being gobbled up by bacteria and “dispersed” by Corexit. In reality, there is no correcting it; the impact is permanent and devastating, in water or on land. But the spill is only visible evidence of our addiction, the minor overdose before the junkie scores again.

As a child, I remember looking from the car windows on road trips at giant mechanical dinosaurs drinking the fluids of their ancestor’s remains from the center of the earth. These same road trips would often leave me sick, with crushing, nauseous migraines induced by a sensitivity to the fumes from those same burning fluids. The sheer multiplicity of material forms crude oil takes on in just those remembered road trips is akin to bathing in the stuff: the gasoline the car is powered by and the oil coursing through it’s engine, the tar in the asphalt under the wheels, the plastic of the car seats and car parts and containers and water bottles and plastic bags and polyester fabric in our clothing and the upholstery...and before the car, with Dad rousting us early to go we encountered the shower curtain, the shampoo, the contact lenses in our eyes, the antihistamine for our allergies, the soap and deodorant, the soles of our shoes…all of it. Ending oil is not as simple as driving less. Americans are responsible for using around three and a half gallons of petroleum per day, even when we stay home. Petroleum is ubiquitous, one can scarcely imagine modern life without it.

We are bringing to the surface our interior, endlessly, though it is not endless. Drawing out the center of our earth like blood from a body, yet there is no rapid regeneration, no stem cells replacing what is lost, nothing fixed by orange juice and a cookie. We leave these drippings of our lifestyles, our existence, in clots on the sea, in dribbles across the landscape, from nano-particles to giant pools. We bring forth the material from underground and lay it across the body of the land like an oozing, blood-encrusted scar, and return it to the earth as tidbits for sea birds to feed to their young on remote islands, and mountains of garbage that children scramble over in other countries. Our appetite is voracious.

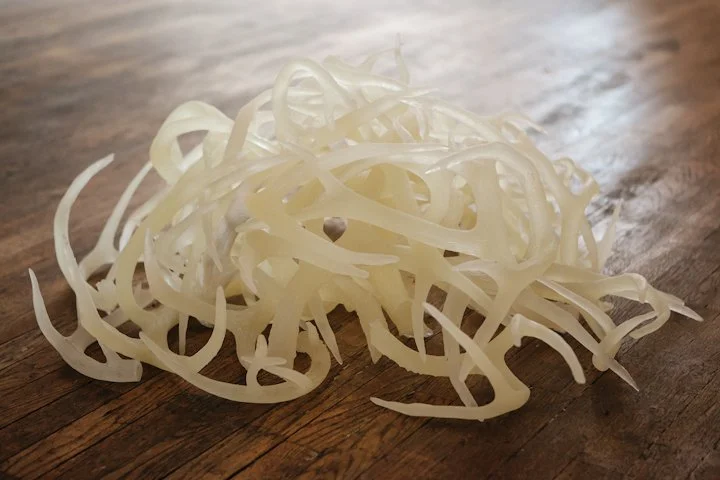

The lament is one of our oldest art forms, left to turn to when our grief and horror overcomes us. These works are my lament, for a planet we have abused and bled dry. And yet, even in making this lament, I am a creature of the modern world; I turn to the materiality of my subject, petroleum. From paintings made with asphaltum (or, as known outside of the printmaking world, bitumen, which flows through the tar sands pipelines) on Yupo, a polyethylene paper, to resin, to plastics and to oil itself. These things exist in the world already, I cannot deny their existence nor resist the fascination with them as substances, despite my regrets.

Lament

by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Listen, children:

Your father is dead.

From his old coats

I'll make you little jackets;

I'll make you little trousers

From his old pants.

There'll be in his pockets

Things he used to put there,

Keys and pennies

Covered with tobacco;

Dan shall have the pennies

To save in his bank;

Anne shall have the keys

To make a pretty noise with.

Life must go on,

And the dead be forgotten;

Life must go on,

Though good men die;

Anne, eat your breakfast;

Dan, take your medicine;

Life must go on;

I forget just why.